Post-quantum Signatures

The state of many signatures

The algorithms to standardize of the Post-Quantum NIST standarisation process are out! We have:

For Public-Key Encryption/KEMs:

- CRYSTALS-KYBER

For Digital Signatures:

- CRYSTALS-Dilithium

- Falcon

- SPHINCS+

With a note:

“CRYSTALS-KYBER (key-establishment) and CRYSTALS-Dilithium (digital signatures) were both selected for their strong security and excellent performance, and NIST expects them to work well in most applications. Falcon will also be standardized by NIST since there may be use cases for which CRYSTALS-Dilithium signatures are too large. Additionally, SPHINCS+ will be standardized to avoid only relying on the security of lattices for signatures. NIST asks for public feedback on a version of SPHINCS+ with a lower number of maximum signatures.”

NIST will also hold a new call for proposals for public key signatures:

“NIST also plans to issue a new Call for Proposals for public-key (quantum-resistant) digital signature algorithms by the end of summer 2022. NIST is primarily looking to diversify its signature portfolio, so signature schemes that are not based on structured lattices are of greatest interest. NIST would like submissions for signature schemes that have short signatures and fast verification (e.g., UOV).”

In this blog post, I’ll be not focusing on the post-quantum KEM, but rather on post-quantum signatures as this seems to be ‘long-road-ahead’ from both a migration perspective as from standardization.

So, let’s explore what post-quantum signatures are available.

The Zoo of Signatures

The lattices

Two of the “winners” of the post-quantum process are lattice-based:

- Dilithium follows the Lyubashevsky’s Fiat–Shamir with aborts framework. Its security is based on the Module-LWE assumption.

- Falcon follows the hash-and-sign framework of Gentry, Peikert and Vaikuntanathan framework. Its security is based on the hardness of the SIS Problem over NTRU lattices.

Dilithium is considered to be “simpler to implement”, but has significant bigger sizes when compared with non-post-quantum signatures. Falcon, on the other hand, has better signing and verification times, and its parameters are smaller than Dilithium (though, they are bigger than non-post-quantum signatures). Falcon also uses constant-time floating point arithmetic, which could be difficult to implement. Falcon also does not provide, as it is, the “beyond unforgeability” security property. In terms of speed, they both seem to outperform implementations of non-post-quantum algorithms.

While they both seem suitable for the ‘online’ signature of a TLS 1.3 handshake (the signature of the handshake), it is unclear if they will work for the whole certificate chain (which involves many other signatures that are generated in an “offline” manner but, sometimes, verified online). Even if we put the performance time’s of the operations aside, the transmission of long parameters as part of the certificate chain can have impact on the latency of TLS connections. We are unclear on how much that impact will be noticable for end-users and if there are mechanisms that we can use to prevent it (caching, supressing intermidiates, zero-knowledge-like proofs of the whole chain, etc.). Some notes around the matter can be found here and here.

For other protocols, they might fail. For DNSSEC, for example, public key and signatures sizes have to be small. From the two, only Falcon’s parameters fall within the size limit needed for DNSSEC, but leaves no room for shipping more than one key/signature at a time or extra payload. For an interesting research around the matter see ‘Retrofitting Post-Quantum Cryptography in Internet Protocols: A Case Study of DNSSEC’ or some notes here.

There is a “simpler-to-implement” version of Falcon, Mitakaya, which manages to avoid floating point arithmetic in one version.

Recently, a very interesting paper has been proposed to reduce the size of lattice-based signatures by sampling according to a suitably chosen ellipsoidal discrete Gaussian rather than a spherical one. This technique reduces the signature size of Falcon by 30–40%. This technique seems very interesting and a very nice avenue of research.

So, it seems like we might see in the future improvements to the lattice schemes.

The alternative that got broken and some news

An interesting candidate that was part of the process was ‘Rainbow’, which uses a multivariate approach.

It is based on the Unbalanced Oil and Vinegar (UOV) scheme.

The signature size was perfect for usage in DNSSEC (and TLS 1.3) but the public key size was not able to fit a DNS packet.

Unfortunately, Rainbow was broken: the attack returns the private key after on average 53 hours (which is basically, one weekend).

But there is another candidate from UOV schemes: MAYO, which has very nice performance and sizes (bigger than non-postquantum-schemes though). This might be a nice contender in the future if its performance is improved.

The MPC ones

Picnic was a candidate for standardisation that will no longer be considered in the NIST process.

It is a non-interactive zero-knowledge proof of knowledge of a private key bound to the message being signed.

Its security is based on the hash function and on the security of the LowMC block cipher.

There has been a lot of research on its security, which has found several weak points (listing the ones I’ve read so far, but there are more).

On the positive news: there is hope. Several variants of Picnic have been proposed that are based on AES. There is BBQ, Banquet, and much more. This very interesting area of research can also lead to a signature scheme with small public keys (as Picnic has).

The isogenies

The security of isogeny schemes falls on the hardness of finding a path in the l-isogeny supersingular graph between two given vertices, which is said to be hard for both classical and quantum computers.

The KLPT algorithm (from Kohel, Lauter, Petit and Tignol) solves the quaternion analog of this problem under the Deuring correspondence.

Based on it, Galbraith, Petit and Silva gave the first theoretical signature scheme related to isogeny graphs of supersingular elliptic curves.

Building on the latter, SQISign was proposed. The scheme has the best parameters of all the post-quantum schemes (mainly, they are small), but its performance is slow. Recently, there has been efforts to improve its performance.

Isogeny-based cryptography is an active area of research. Interesting candidates might come from this area.

Hash-based

There are two “types” here: schemes that maintain state (XMSS or LMS) and schemes that are state-less (SPHINCS+).

Both types use the same security assumption: security of the underlying hash function used.

The reason why there are two types is that some applications might not be able to maintain state (and need careful consideration for doing so), and, hence, will benefit from using SPHINCS+.

Nevertheless, SPHINCS+ has larger signature sizes.

Great documentation of hash-based schemes can be found here.

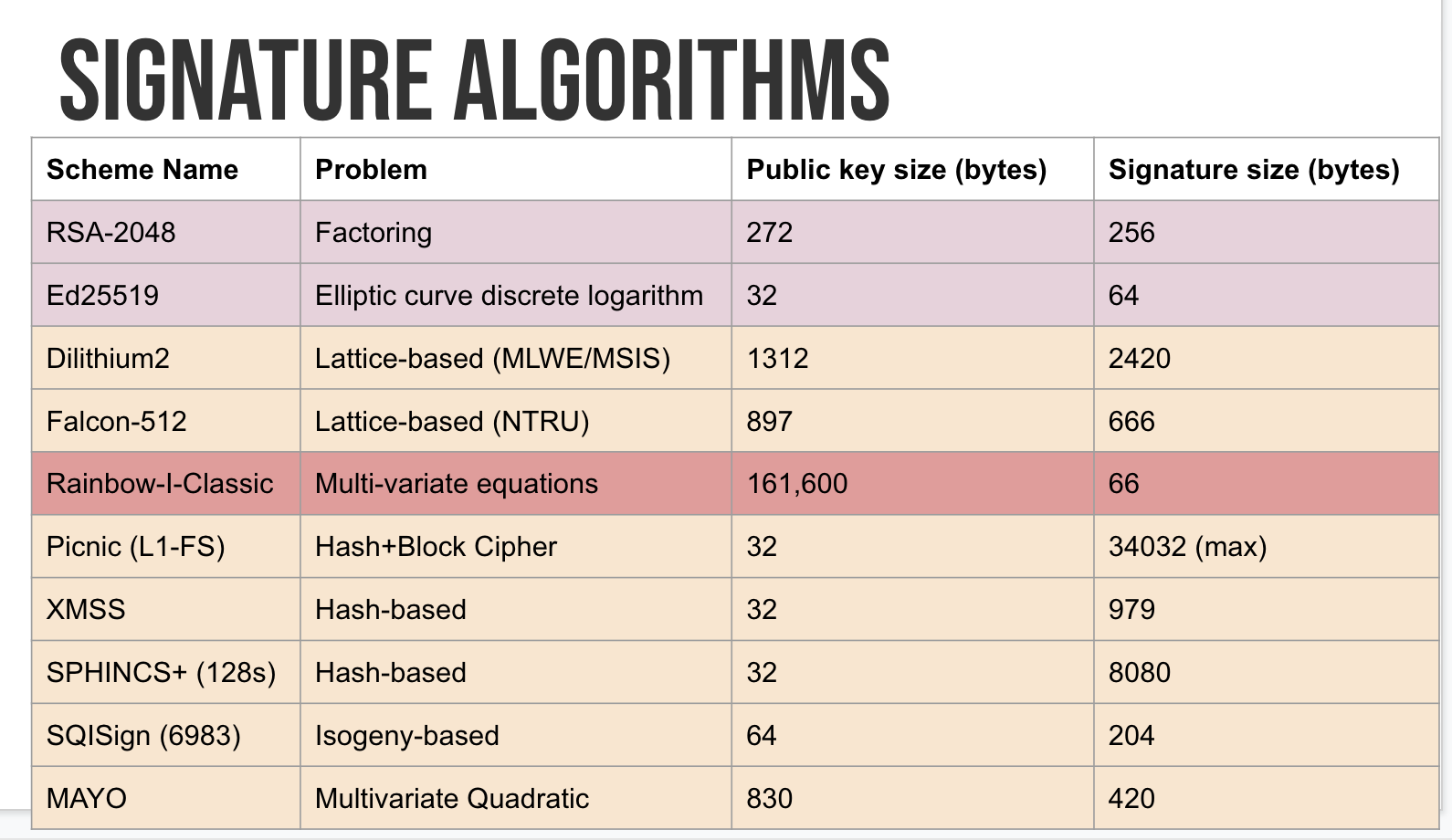

A table of comparison of sizes:

So, lots of avenues of research are still open for a post-quantum signature scheme that work on the protocols we use nowadays. Let the science begin!

EDIT: Thank you Peter Schwabe, Andreas Hülsing, Gustavo Banegas and Carsten Baum for pointing out additions needed and fixes to be made.